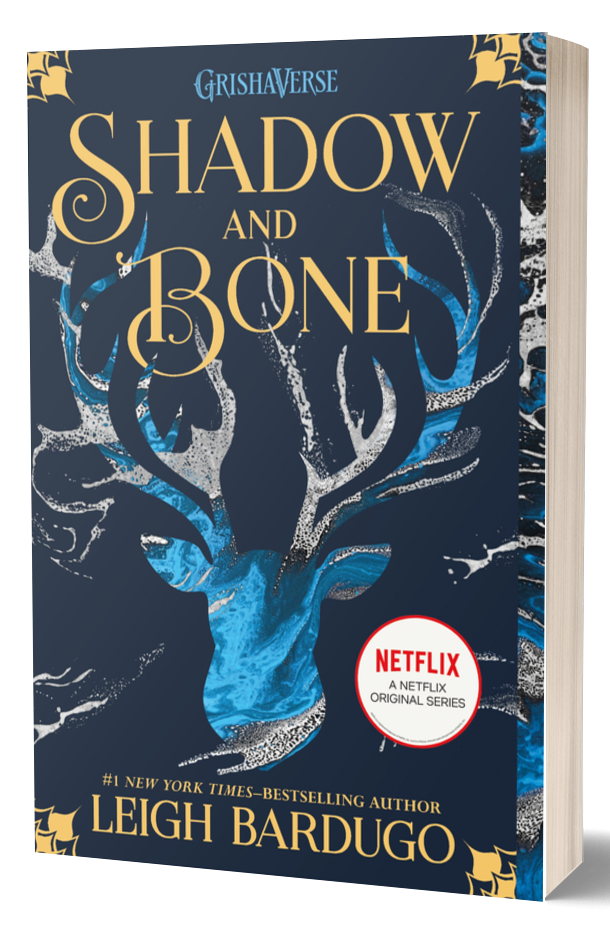

Shadow and Bone:

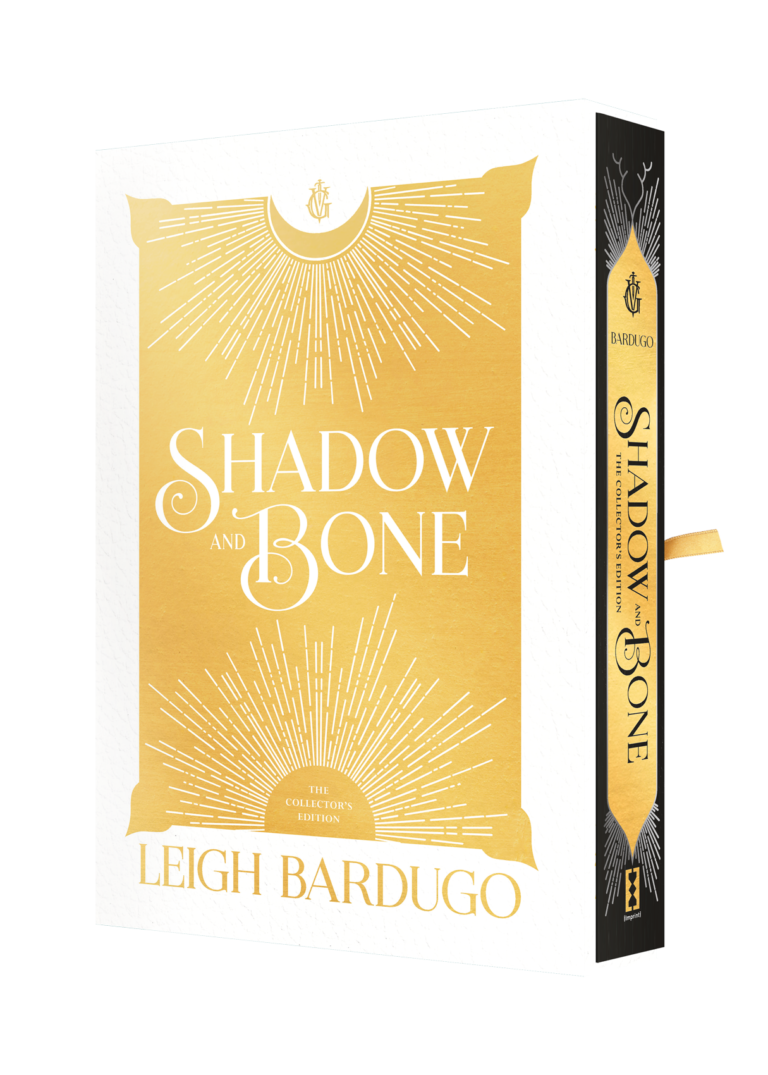

The Collector’s Edition

Read from the beginning with this beautiful deluxe collector’s edition of the first novel in the worldwide-bestselling Shadow and Bone Trilogy by Leigh Bardugo. This edition features brand-new artwork, a hardcover slipcase with exclusive design, a ribbon pull, and more.