King of Scars Duology

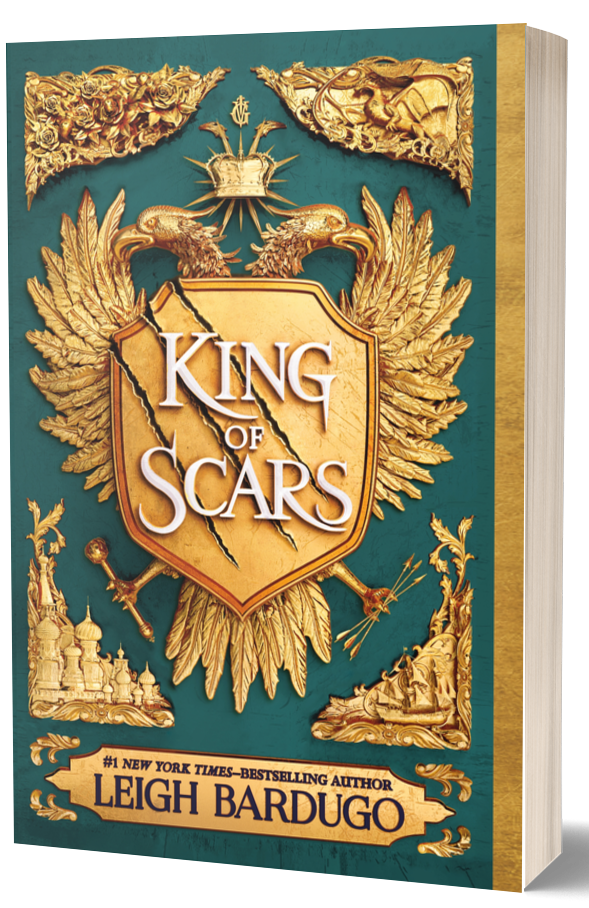

King of Scars

The adventure continues in the first book of this explosive duology. Young King Nikolai Lantsov confronts the dark magic within him that threatens to consume his very soul. To vanquish his inner demons, he will undertake a journey through the realm to where the deepest magic survives—and risk everything to save his country and himself.

Nikolai Lantsov has always had a gift for the impossible. No one knows what he endured in his country’s bloody civil war―and he intends to keep it that way. Now, as enemies gather at his weakened borders, the young king must find a way to refill the nation’s coffers, forge new alliances, and stop a rising threat to the once-great Grisha Army.

Yet every day a dark magic within him grows stronger, threatening to destroy all he has built. With the help of a young monk and a legendary Grisha Squaller, Nikolai will journey to where the deepest magic survives to vanquish the terrible legacy inside him. He will risk everything to save his country and himself. But some secrets aren’t meant to stay buried―and some wounds aren’t meant to heal.

"[Bardugo] touches on religion, class, family, love — all organically, all effortlessly, all cloaked in the weight of a post-war reckoning with the cost (literal and figurative) of surviving the events that shape both people and nations." —NPR

"Deadly clever political intrigue, heart-stopping adventure, memorable characters, and several understated, hinted-at romances (how will we wait?!) come together in one glorious, Slavic-folklore infused package. Bardugo's star continues to rise." —Booklist, starred review

"The sharp dialogue and lovable characters continue to enthrall and bewitch long past the final chapter. With twists and revelations cleverly dispersed up until the very last page, this novel is a must-have for any book shelf." —School Library Journal, starred review

"A richly detailed and refreshingly diverse world inhabited by individuals who, for all their magical talents, are resonantly human." —The Washington Post

Buy the Book

Hardcover

Book Excerpt

1 Dima

Dima heard the barn doors slam before anyone else did. Inside the little farmhouse, the kitchen bubbled like a pot on the stove, its windows shut tight against the storm, the air in the room moist and warm. The walls rattled with the rowdy din of Dima’s brothers talking over one another, as his mother hummed and thumped her foot to a song Dima didn’t know. She held the torn sleeve of one of his father’s shirts taut in her lap, her needle pecking at the fabric in the uneven rhythm of an eager sparrow, a skein of wool thread trailing between her fingers like a choice worm.

Dima was the youngest of six boys, the baby who had arrived late to his mother, long after the doctor who came through their village every summer had told her there would be no more children. An unexpected blessing, Mama liked to say, holding him close and fussing over him when the others had gone off to their chores. An unwanted mouth to feed, his older brother Pyotr would mutter.

Because Dima was so small, he was often left out of his brothers’ jokes, forgotten in the noisy arguments of the household, and that was why, on that autumn night, standing by the basin, soaping the last of the pots that his brothers had made sure to leave for him, he heard the damning thunk of the barn doors. Dima set to scrubbing harder, determined to finish his work and get to bed before anyone could think to send him out into the dark. He could hear their dog, Molniya, whining on the kitchen stoop, begging for scraps and a warm place to sleep as the wind rose on an angry howl.

Branches lashed the windows. Mama lifted her head, the grim furrows around her mouth deepening. She scowled as if she could send the wind to bed without supper. “Winter comes early and stays too long.”

“Hmm,” said Papa, “like your mother,” and Mama gave him a kick with her boot.

She’d left a little glass of kvas behind the stove that night, a gift for the household ghosts who watched over the farm and who slept behind the old iron stove to keep warm. Or so Mama said. Papa only rolled his eyes and complained it was a waste of good kvas.

Dima knew that when everyone had gone to bed, Pyotr would slurp it down and eat the slice of honey cake Mama left wrapped in cloth. “Great-grandma’s ghost will haunt you,” Dima sometimes warned. But Pyotr would just wipe his sleeve across his chin and say, “There is no ghost, you little idiot. Baba Galina was lunch for the cemetery worms, and the same thing will happen to you if you don’t keep your mouth shut.”

Now Pyotr leaned down and gave Dima a hard jab. Dima often wondered if Pyotr did special exercises to make his elbows more pointy. “Do you hear that?” his brother asked.

“There’s nothing to hear,” said Dima as his heart sank. If Pyotr had heard the barn doors . . .

“Something is out there, riding the storm.”

So his brother was just trying to scare him. “Don’t be stupid,” Dima said, but he was relieved.

“Listen,” said Pyotr, and as the wind shook the roof of the house and the fire sputtered in the grate, Dima thought he heard something more than the storm, a high, distant cry, like the yowl of a hungry animal or the wailing of a child. “When the wind blows through the graveyard, it wakes the spirits of all the babies who died before they could be given their Saints’ names. Malenchki.They go looking for souls to steal so they can barter their way into heaven.” Pyotr leaned down and poked his finger into Dima’s shoulder. “They always take the youngest.”

Dima was eight now, old enough to know better, but still his eyes strayed to the dark windows, out to the moonlit yard, where the trees bowed and shook in the wind. He flinched. He could have sworn—just for a moment, he could have sworn he saw a shadow streak across the yard, the dark blot of something much larger than a bird.

Pyotr laughed and splashed him with soapy water. “I swear you get more witless with every passing day. Who would want your little nothing of a soul?”

Pyotr angry because,before you, he was the baby, Mama always told Dima. You must try to be kind to your brother even when he is older but not wiser. Dima tried. He truly did. But sometimes he just wanted to knock Pyotr on his bottom and see how he liked feeling small.

The wind dropped and in the sudden gust of silence, there was no disguising the sharp slam that echoed across the yard.

“Who left the barn doors open?” Papa asked.

“It was Dima’s job to see to the stalls tonight,” Pyotr said virtuously, and his brothers, gathered around the table, clucked like flustered hens.

“I closed it,” protested Dima. “I set the bar fast!”

Papa leaned back in his chair. “Then do I imagine that sound?”

“He probably thinks a ghost did it,” said Pyotr.

Mama looked up from her mending. “Dima, you must go close and bar the doors.”

“I will do it,” said Pyotr with a resigned sigh. “We all know Dima is afraid of the dark.”

But Dima sensed this was a test. Papa would expect him to take responsibility. “I am not afraid,” he said. “Of course I will go close the doors.”

Dima ignored Pyotr’s smug look; he wiped his hands and put on his coat and hat. Mama handed him a tin lantern. “Hurry up, now,” she said, pushing up his collar to keep his neck warm. “Scurry back and I’ll tuck you in and tell you a story.”

“A new one?”

“Yes, and a good one, about the mermaids of the north.” “Does it have magic in it?”

“Plenty. Go on, now.”

Dima cast his eyes once to the icon of Sankt Feliks on the wall by the door, candlelight flickering over his sorrowful face, his gaze full of sympathy as if he knew just how cold it was outside. Feliks had been impaled on a spit of apple boughs and cooked alive just hours after he’d performed the miracle of the orchards. He hadn’t screamed or cried, only suggested that the villagers turn him so that the flames could reach his other side. Feliks wouldn’t be afraid of a storm.

As soon as Dima opened the kitchen door, the wind tried to snatch it from his grip. He slammed it behind him and heard the latch turn from the other side. He knew it was temporary, a necessity, but it still felt like he was being punished. He looked back at the glowing windows as he forced his feet down the steps to the dry scrabble of the yard, and had the terrible thought that as soon as he’d left the warmth of the kitchen his family had forgotten him, that if he never returned, no one would cry out or raise the alarm. The wind would wipe Dima from their memory.

He considered the long moonlit stretch he would have to traverse past the chicken coops and the goose shed to the barn, where they sheltered their old horse, Gerasim, and their cow, Mathilde.

The geese honked and rustled in their shed, riled by the weather or Dima’s nervous footsteps as he passed. Ahead, he saw the big wooden barn doors swaying open and shut as if the building was sighing, as if the doorway was a mouth that might suck him in with a single breath. He liked the barn in the day, when sunlight fell through the slats of the roof and everything was hay smells, Gerasim’s snorting, Mathilde’s disapproving moo. But at night, the barn became a hollow shell, an empty place waiting for some terrible creature to fill it—some cunning thing that might let the doors blow open to lure a foolish boy outside. Because Dima knew he had closed those doors. He felt certain of it, and he could not help but think of Pyotr’s malenchki, little ghosts hunting for a soul to steal.

Stop it, Dima scolded himself. Pyotr unbarred the doors himself just so you would have to go out in the cold or shame yourself by refusing. But Dima had shown his brothers and his father that he could be brave, and that thought warmed him even as he yanked his collar up around his ears and shivered at the bite of the wind. Only then did he realize he couldn’t hear Molniya barking anymore. She hadn’t been by the door, trying to nose her way into the kitchen, when Dima ventured outside.

“Molniya?” he said, and the wind seized his voice, casting it away. “Molniya!” he called, but only a bit louder—in case something other than his dog was out there listening.

Step by step he crossed the yard, the shadows from the trees leaping and shuddering over the ground. Beyond the woods he could see the wide ribbon of the road. It led all the way to the town, all the way to the churchyard. Dima did not let his eyes follow it. It was too easy to imagine some shambling body dressed in ragged clothes traveling the road, trailing clods of cemetery earth behind it.

He heard a soft whine from somewhere in the trees. Dima yelped. Yellow eyes stared back at him from the dark. The glow from his lantern fell on a pair of black paws, ruffled fur, bared teeth.

“Molniya!” he said on a relieved sigh of breath. He was grateful for the loud moan of the storm. The thought of his brothers hearing his high, shameful shriek and coming running just to find his poor dog cowering in the brush was too horrible to contemplate. “Come here, girl,” he coaxed. Molniya had pressed her belly to the ground; her ears lay flat against her head. She did not move.

p>Dima looked back at the barn. The plank that should have lain across the doors and kept them in place lay smashed to bits in the brush. From somewhere inside, he heard a soft, wet snuffling. Had a wounded animal found its way inside? Or a wolf?

The golden light of the farmhouse windows seemed impossibly far away. Maybe he should go back and get help. Surely he couldn’t be expected to face a wolf by himself. But what if there was nothing inside? Or some harmless cat that Molniya had gotten a piece of? Then all his brothers would laugh at him, not just Pyotr.

Dima shuffled forward, keeping his lantern far out in front of him. He waited for the storm to quiet and grabbed the heavy door by its edge so it would not strike him as he entered.

The barn was dark, barely touched by slats of moonlight. Dima edged a little deeper into the blackness. He thought of Sankt Feliks’s gentle eyes, the apple bough piercing his heart. Then, as if the storm had just been catching its breath, the wind leapt. The doors behind Dima slammed shut and the weak light of his lantern sputtered to nothing.

Outside, he could hear the storm raging, but the barn was quiet. The animals had gone silent as if waiting, and he could smell their sour fear over the sweetness of the hay— and something else. Dima knew that smell from when they slaughtered the geese for the holiday table: the hot copper tang of blood.

Go back, he told himself.

In the darkness, something moved. Dima caught a glint of moonlight, the shine of what might have been eyes. And then it was as if a piece of shadow broke away and came sliding across the barn.

Dima took a step backward, clutching the useless lantern to his chest. The shadow wore the shredded remains of what might have once been fine clothes, and for a brief, hopeful moment, Dima thought a traveler had stumbled into the barn to sleep out the storm. But it did not move like a man. It was too graceful, too silent, as its body unwound in a low crouch. Dima whimpered as the shadow prowled closer. Its eyes were mirror black, and dark veins spread from its clawed fingertips as if its hands had been dipped in ink. The tendrils of shadow tracing its skin seemed to pulse.

Run, Dima told himself. Scream. He thought of the way the geese came to Pyotr so trustingly, how they made no sound of protest in the scant seconds before his brother broke their necks. Stupid, Dima had thought at the time, but now he understood.

The thing rose from its haunches, a black silhouette, and two vast wings unfurled from its back, their edges curling like smoke.

“Papa!” Dima tried to cry, but the word came out as little more than a puff of breath.

The thing paused as if the word was somehow familiar. It listened, head cocked to the side, and Dima took another step backward, then another.

The monster’s eyes snapped to Dima and the creature was suddenly bare inches away, looming over him. With the gray moonlight falling over its body, Dima could see that the dark stains around its mouth and on its chest were blood.

The creature leaned forward, inhaling deeply. Up close it had the features of a young man—until its lips parted, the corners of its mouth pulling back to reveal long black fangs.

It was smiling. The monster was smiling—because it knew it would soon be well fed. Dima felt something warm slide down his leg and realized he had wet himself.

The monster lunged.

The doors behind Dima blew open, the storm demanding entry. A loud crack sounded as the gust knocked the creature from its clawed feet and hurled its winged body against the far wall. The wooden beams splintered with the force, and the thing slumped to the floor in a heap.

A figure strode into the barn in a drab gray coat, a strange wind lifting her long black hair. The moon caught her features, and Dima cried harder, because she was too beautiful to be any ordinary person, and that meant she must be a Saint. He had died and she had come to escort him to the bright lands.

But she did not stoop to take him in her arms or murmur soft prayers or words of comfort. Instead she approached the monster, hands held out before her. She was a warrior Saint, then, like Sankt Juris, like Sankta Alina of the Fold.

“Be careful,” Dima managed to whisper, afraid she would be harmed. “It has . . . such teeth.”

But his Saint was unafraid. She nudged the monster with the toe of her boot and rolled it onto its side. The creature snarled, and Dima clutched his lantern tighter as if it might become a shield.

In a few swift movements, the Saint had secured the creature’s clawed hands in heavy shackles. She yanked hard on the chain, forcing the monster to its feet. It snapped its teeth at her, but she did not scream or cringe. She swatted the creature on its nose as if it were a misbehaving pet.

The thing hissed, pulling futilely on its restraints. Its wings swept once, twice, trying to lift her off her feet, but she gripped the chain in her fist and thrust her other hand forward. Another gust of wind struck the monster, slamming it into the barn wall. It hit the ground, fell to its knees, stumbled back up, weaving and unsteady in a way that made it seem curiously human, like Papa when he had been out late at the tavern. The Saint murmured something and the creature hissed again as the wind eddied around them.

Not a Saint, Dima realized. Grisha. A soldier of the Second Army. A Squaller who could control wind.

She took her coat and tossed it over the creature’s head and shoulders, leading her captured prey past Dima, the monster still struggling and snapping.

She tossed Dima a silver coin. “For the damage,” she said, her eyes bright as jewels in the moonlight. “You saw nothing tonight, understood? Hold your tongue or next time I won’t keep him on his leash.”

Dima nodded, feeling fresh tears spill down his cheeks. The Grisha raised a brow. He’d never seen a face like hers, more lovely than any painted icon, blue eyes like the deepest waters of the river. She tossed him another coin, and he just managed to snatch it from the air. “That one’s for you. Don’t share it with your brothers.”

Dima watched as she vanished through the barn doors, then forced his feet to move. He wanted to return to the house, find his mother, and bury himself in her skirts, but he was desperate for one last look at the Grisha and her monster. He trailed after them as silently as he could. In the shadows of the moonlit road, a large coach waited, the driver cloaked in black. A coachman jumped down and seized the chain, help- ing to drag the creature inside.

Dima knew he must be dreaming, despite the cool weight of silver in his palm, because the coachman did not look at the monster and say Go on, you beast! or You’ll never trouble these people again! as a hero would in a story.

Instead, in the deep shadows cast by the swaying pines, Dima thought he heard the coachman say, “Watch your head, Your Highness.”

2

Zoya

The stink of blood hung heavy in the coach. Zoya pressed her sleeve to her nose to ward off the smell, but the musty odor of dirty wool wasn’t much improvement.

Vile. It was bad enough that she had to go tearing off across the Ravkan countryside in the dead of night in a borrowed, badly sprung coach, but that she had to do so in a garment like this? Unacceptable. She stripped the coat from her body. The stench still clung to the silk of her embroidered blue kefta, but she felt a bit more like herself now.

They were ten miles outside Ivets, nearly one hundred miles from the safety of the capital, racing along the narrow roads that would lead them back to the home of their host for the trade summit, Duke Radimov. Zoya wasn’t much for praying, so she could only hope no one had seen Nikolai escape his chambers and take to the skies. If they’d been back home, back in the capital, this never would have happened.

The horse’s hooves thundered, the wheels of the coach clattering and jouncing, as beside her the king of Ravka gnashed his needle-sharp teeth and pulled at his chains.

Zoya kept her distance. She’d seen what one of Nikolai’s bites could do when he was in this state, and she had no interest in losing a limb or worse. Part of her had wanted to ask Tolya or Tamar to ride inside the carriage with her until Nikolai resumed his human form. But she knew what that would cost him. It was bad enough that she should witness his misery.

Outside, the wind howled. It was less the baying of a beast than the high, wild laugh of an old friend, driving them on. The wind did what she willed it, had since she was a child, but on nights like these, she couldn’t help but feel that it was not her servant but her ally: a storm that rose to mask a creature’s snarls, to hide the sounds of a fight in a rickety barn, to whip up trouble in streets and village taverns. This was the western wind, Adezku the mischief-maker. Even if that boy told everyone in Ivets what he’d seen, they’d chalk it up to Adezku, the rascal wind that drove women into their neighbors’ beds and made mad thoughts skitter in men’s heads like whorls of dead leaves.

A mile later, the snarls in the coach had quieted; the chains did not clank as the creature seemed to sink further and further into the shadows of the seat. At last, a voice, hoarse and beleaguered, said, “I don’t suppose you brought me a fresh shirt?”

Zoya took the pack from the coach floor and pulled out a clean white shirt and fur-lined coat, both finely made but thoroughly rumpled, appropriate attire for a royal who had spent the night carousing.

Silently, Nikolai held up his shackled wrists. The talons had retracted, but his hands were still scarred with the faint black lines he had borne since the end of the civil war. The king often wore gloves to hide them, and Zoya thought that was a mistake. The scars were a reminder of the torture he had endured at the hands of the Darkling, that he had paid a price alongside his country. Of course, that was only part of the story, but it was the part the Ravkan people were best equipped to handle.

Zoya unlocked the chains with the heavy key she wore around her neck. She hoped it was her imagination, but the scars on Nikolai’s hands seemed darker lately, as if determined not to fade.

Once his hands were free, Nikolai peeled the ruined shirt from his body. He used the linen and water from the flask she handed him to wash the blood from his chest and mouth. He splashed more over his hands and ran them through his hair, the water trickling down his neck and shoulders. He was shaking badly.

“Where did you find me this time?” he asked, keeping most of the tremor from his voice.

Zoya wrinkled her nose at the memory. “A goose farm.” “I hope it was one of the more fashionable goose farms.”

He fumbled with the buttons of his clean shirt, fingers trembling. “Do we know what I killed?”

Or who? The question hung unspoken in the air.

Zoya batted Nikolai’s quaking hands away from his buttons and took up the work herself. Through the thin cotton, she could feel the cold the night had left on his skin.

“What an excellent valet you make,” he murmured. But she knew he hated submitting to these small attentions, that he was weak enough to require them.

Sympathy would only make it worse, so she kept her voice brusque. “I presume you killed a great deal of geese. Possibly a shaggy pony.” But had that been all? Zoya had no way of knowing what the monster might have gotten into before they’d found him. “You remember nothing?”

“Only flashes.”

They would just have to wait for any reports of deaths or mutilations. The trouble had begun six months earlier, when Nikolai had woken in a field nearly thirty miles from Os Alta, bloodied and covered in bruises, with no memory of how he’d gotten out of the palace or what he’d done in the night. I seem to have taken up sleepwalking, he’d declared to Zoya and the rest of the Triumvirate when he’d sauntered in late to their morning meeting, a long scratch down his cheek. They’d been concerned but also baffled. His personal guards, the twins Tolya and Tamar, were hardly the type to just let Nikolai slip by. He’d had new locks placed on his bedroom doors and insisted they move on to the business of the day. Three weeks later, Tolya had been reading in a chair outside the king’s bedchamber when he’d heard the sound of breaking glass and burst through the door to see Nikolai leap from the window ledge, his back split by wings of curling shadow.

p>Tolya had woken Zoya and they’d tracked the king to the roof of a grainery fifteen miles away. They had started chaining the king to his bed—an effective solution, workable only because Nikolai’s servants were not permitted inside his bedchamber at the palace. The king was a war hero, after all, and known to suffer nightmares. For six months, Zoya had locked him in every night and released him every morning, and they’d kept Nikolai’s secret safe. Only Tolya, Tamar, and the Grisha Triumvirate knew the truth. If anyone discovered the king of Ravka spent his nights trussed up in chains, he’d be a perfect target for assassination or coup, not to mention a laughingstock.

That was what made travel so dangerous. But Nikolai had refused to stay sequestered behind the walls of Os Alta.

“A king cannot remain locked up in his own castle,” he’d declared. “One risks looking less like a monarch and more like a hostage.”

“You have emissaries to manage these matters of state,” Zoya had argued, “ambassadors, underlings.”

“The public may forget how handsome I am.” “I doubt it. Your face is on the money.”

But Nikolai had refused to relent, and Zoya could admit he wasn’t entirely wrong. His father had made the mistake of letting others conduct the business of ruling, and it had cost him.

Because Nikolai and Zoya couldn’t very well travel with a trunk full of chains for inquisitive servants to discover, whenever they were away from the safety of the palace, they relied on a powerful sedative to keep Nikolai tucked into bed and the monster at bay.

“Genya will have to mix my tonic stronger,” he said, shrugging into his coat.

“Or you could stay in the capital and cease taking these foolish risks.” So far the monster had been content with attacks on livestock, his casualties limited to gutted sheep and drained cattle. But they both knew it was only a question of time. Whatever the Darkling’s power had left seething within Nikolai hungered for more than animal flesh.

“The last incident was barely a week ago.” He scrubbed a hand over his face. “We should have had more time.”

“It’s getting worse.”

“I like to keep you on your toes, Nazyalensky. Constant anxiety does wonders for the complexion.”

“I’ll send you a thank-you card.”

“Make sure of it. You’re positively glowing.”

They heard a sharp whistle from outside as the carriage slowed.

“We’re approaching the bridge,” Zoya said.

The trade summit in Ivets had been essential to their negotiations with Kerch and Novyi Zem, but the business of tariffs and taxes had also provided cover for their true mission: a visit to the site of Ravka’s latest miracle.

A week ago, the villagers of Ivets had set out behind Duke Radimov’s ribbon-festooned cart to celebrate the Festival of Sankt Grigori, banging drums and playing little harps meant to mimic the instrument Grigori had fashioned to soothe the beasts of the forest. But when they’d reached the Sokol, the wooden bridge that spanned the river gorge had given way. Before the duke and his vassals could plummet to the raging whitewater below, another bridge had sprung up beneath them, seeming to bloom from the very walls of the chasm and the jagged rocks of the canyon floor.

Zoya peered out the coach window as they rounded the road and the new bridge came into view, its tall, slender pillars and long girders gleaming white in the moonlight. She’d seen it before, walked its length with the king, but the sight was still astonishing. From a distance, it looked like something wrought in alabaster. It was only when one drew closer that it became clear the bridge was not stone at all.

Nikolai shook his head. “As a man who regularly turns into a monster, I realize I shouldn’t be making judgments, but are we sure it’s stable?”

“No,” said Zoya, forcing her breathing to steady and her fists to unclench, “but it’s the only way across the gorge.”

“Perhaps I should have brushed up on my prayers.”

The sound of the wheels changed as the coach rolled onto the bridge, from the rumble of the road to a steady thump, thump, thump. The bridge that had so miraculously sprung up from nothing was not stone or brick or wooden beam. Its white girders and transoms were bone and tendon, its abutments and piers bound together with ropy bundles of gristle. Thump, thump, thump. They were traveling over a spine.

“I don’t care for that sound,” said Zoya.

“Agreed. A miracle should sound more dignified. Some chimes, perhaps, or a choir of heavenly voices.”

“Don’t call it that,” snapped Zoya. “A choir?”

“A miracle.” Zoya had whispered enough futile prayers in her childhood to know the Saints never answered. The bridge was Grisha craft and there was an explanation for its appearance that she intended to find.

“What would you call a bridge made of bones appearing just in time to save an entire town from death?”

“It wasn’t an entire town.”

“Half a town,” amended Nikolai. “An unexpected occurrence.”

“That doesn’t quite do this marvel justice.”

And it was a marvel. At once elegant and grotesque, a mass of crossing beams and soaring arches. Since it had appeared, pilgrims had camped at either end of it, holding vigil day and night. They did not raise their heads as the coach rolled by.

“What would you call the earthquake in Chernast?” Nikolai asked. “Or the statue of Sankta Anastasia weeping tears of blood outside Tsemna?”

“Trouble,” Zoya said. The occurrences had begun right around the same time as Nikolai’s night spells. It might be a coincidence, but it seemed possible that the strange happenings in their country were tied to the power burdening their king. They had come to Ivets in the hopes of finding some clue, some connection that might help them rid Nikolai of the monster’s will.

“You still think it’s the work of Grisha using parem?” he asked. “How else would someone create such a bridge or an earthquake on demand?”

Parem. The drug was the product of experimentation in a Shu lab. It could take a Grisha’s power and transform it into something wholly new and wholly dangerous. It might make it possible for a rogue Fabrikator to shake the earth or for a Corporalnik to make a bridge out of a body. But to what end? And how was it tied to the dark power that sheltered inside Nikolai? They reached the other side of the bridge, and the reassuringly ordinary rumble of the dirt road filled the coach once more. It was as if a spell had lifted.

“We’ll have to leave Duke Radimov’s today,” said Nikolai. “And hope no one saw me flapping around the grounds.”

Part of Zoya wanted to agree, but since they’d made the journey . . . “I can double your dose. There’s another day left in negotiations.”

“Let Ulyashin handle them. I want to get back to the capital. We have samples from the bridge for David. He may be able to learn something we can use to deal with my . . .”

“Affliction?” “Uninvited guest.”

Zoya rolled her eyes. He spoke as if he were being plagued by a bilious aunt. But there was another reason for them to stay. She tapped her fingers against the velvet seat, uncertain of how to proceed. She’d hoped to orchestrate a meeting between Nikolai and the Schenck girls without him realizing that she was meddling. The king did not like to be led, and when he sensed he was being pushed, he could be just as stubborn as . . . well, as Zoya.

“Speak, Nazyalensky. When you purse your lips like that, you look like you’ve made love to a lemon.”

“Lucky lemon,” Zoya said with a sniff. She smoothed the fabric of her kefta over her lap. “The Schenck family arrives tomorrow.”

“And?”

“They have two daughters.”

Nikolai laughed. “Is that why you agreed to this trip so readily? So that you could indulge in your matchmaking?”

“I agreed because someone has to make sure you don’t eat anyone when your uninvited guest decides to get peckish in the middle of the night. And I am not some interfering mama who wants to see her darling son wed. I am trying to protect your throne. Hiram Schenck is a senior member of the Mer- chant Council. He could all but guarantee leniency on Ravka’s loans from Kerch, to say nothing of the massive fortune one of his pretty daughters will inherit.”

“How pretty?” “Who cares?”

“Not me, certainly. But two years working with you has worn away my pride. I want to make sure I won’t spend my life watching other men ogle my wife.”

“If they do, you can have them beheaded.” “The men or my wife?”

“Both. Just make sure to get her dowry first.” “Ruthless.”

“Practical. If we stayed another night—”

“Zoya, I can’t very well court a bride if there’s a chance I may try to turn her into dinner.”

“You’re a king. The throne and the jewels and the title do the courting for you, and once you’re married, your queen will become your ally.”

“Or she may run screaming from our wedding bower and tell her father I began by nibbling on her earlobe and then tried to consume her actual ear. She could start a war.”

“But she won’t, Nikolai. Because by the time you two have said your vows, you’ll have charmed her into loving you and then you’ll be her problem to take care of.”

“Even my charm has its limits, Zoya.”

If so, she had yet to encounter them. Zoya cast him a disbelieving glance. “A handsome monster husband who put a crownonherhead? It’s aperfect fairy tale to sell to some starry-eyed girl. She can lock you in at night and kiss you sweetly in the morning, and Ravka will be secure.”

“Why do you never kiss me sweetly in the morning, Zoya?”

“I do nothing sweetly, Your Highness.” She shook out her cuffs. “Why do you hesitate? Until you marry, until you have an heir, Ravka will remain vulnerable.”

Nikolai’s glib demeanor vanished. “I cannot take a wife while I am in this state. I cannot forge a marriage founded on lies.”

“Aren’t most?” “Ever the romantic.”

“Practical,” she repeated.

Another sharp whistle sounded from outside the carriage, two quick notes—Tolya’s signal that they were approaching the gatehouse.

Zoya knew there would be some confusion among the guards. No one had seen the coach ride out and it bore no royal seal. Tolya and Tamar had kept it at the ready well outside the duke’s estate just in case Nikolai slipped his leash. She’d gone to find them as soon as she realized he was missing. It was dangerous to check on him in his chambers. She knew the rumors were already thick that their relationship was more than political. It didn’t matter. Worse things had been rumored about leaders before.

They’d gotten lucky tonight. They’d found the king before he’d strayed too far. When Nikolai flew, she could sense him riding the winds and use the disruption in their pattern to track his movements. But if she hadn’t gotten to that farm when she had, what might have happened? Would Nikolai have killed that boy? The thing inside him was not just a hungry animal but something far worse, and she knew with absolute surety that it longed for human prey. Somehow the king had kept its worst impulses at bay, but for how long?

“We cannot go on this way, Nikolai.” Eventually they would be found out. Eventually these evening hunts and sleepless nights would get the best of them. “We must all do what is required.”

Nikolai sighed and opened his arms to her as the coach rattled to a stop. “Then come here, Zoya, and kiss me sweetly as a new bride would.”

So much for propriety. Zoya took a second flask from the pack and dabbed whiskey at her pulse points like perfume before handing it to Nikolai, who took a long swig, then splashed the rest liberally over his coat. Zoya ruffled her hair, let her kefta slip from one shoulder, and eased into the king’s arms. It was an easy role to play, sometimes too easy.

He buried his face in her hair, inhaling deeply. “How is it I smell like goose shit and cheap whiskey and you smell like you just ran through a meadow of wildflowers?”

“Ruthlessness.”

He breathed in again. “What isthat scent? It reminds me of something, but I can’t place what.”

“The last child you tried to eat?” “That must be it.”

The door to the coach flew open.

“Your Highness, we hadn’t realized you’d gone out tonight.” Zoya couldn’t see the guard’s face, but she could hear the suspicion in his voice.

“Your king is not in the habit of asking for anything, least of all permission,” said Nikolai, his voice lazy but with the disdainful edge of a monarch who knew nothing but indulgence. “Of course, of course,” said the guard. “We had only your safety in mind, my king.” Zoya doubted it. Western Ravka had bridled under the new taxes and laws that had come with unification. These guards might wear the double eagle, but their loyalty belonged to the duke who ran this estate and who had thrown up opposition to Nikolai’s rule at every turn. No doubt

their master would be thrilled to uncover the king’s secrets.

Zoya summoned her most plaintive tone and said, “Why aren’t we moving?”

She sensed the shift in their interest.

“A good night, then?” said the guard, and she could almost see him peering into the coach to get a better look.

Zoya tossed her long dark hair and said with the sleepy, tousled sound of a woman well tumbled, “A very good night.” “She only play with royals?” said the guard. “She looks like fun.”

Zoya felt Nikolai tense. She was both touched and annoyed that he thought she cared what some buffoon believed, but there was no need to play at chivalry tonight.

She cast the guard a long look and said, “You have no idea.” He chortled and waved them through.

Zoya expected Nikolai to release her, but as the coach rolled on, he kept his arms around her. She could feel the faint tremor of transformation still echoing through him and her own exhaustion creeping over her. It would be too easy to let her eyes close, to give in to the illusion of comfort. But they could not afford to rest for long. “Eventually someone will see or talk,” she said. “We’ve had no luck in finding a cure. Marry. Forge an alliance. Make an heir. Secure the throne and Ravka’s future.”

“I will,” he said wearily. “I’ll do all of it. But not tonight.

Tonight let’s pretend we’re married.”

If any other man had said such a thing, she would have punched him in the jaw. Or possibly taken him to bed. “And what does that entail?”

“Let’s tell each other lies as married couples do. It will be a good game. Go on, wife. Tell me I’m a handsome fellow who will never age and who will die with all of his own teeth in his head. Make me believe it.”

“I will not.”

“I understand. You’ve never had a talent for deception.” Zoya knew he was goading her, but her pride pricked anyway. “Perhaps the list of my talents is so long you just haven’t gotten to the end.”

“Go on, then, Nazyalensky.”

“Dearest husband,” she said, making her voice honey sweet, “did you know the women of my family can see the future in the stars?”

He huffed a laugh. “I did not.”

“Oh yes. And I’ve seen your fate in the constellations. You will grow old, fat, and happy, father many ill-behaved children, and they will tell your story in legend and song.”

“Very convincing,” Nikolai said. “You’re good at this game.” A long silence followed, filled with nothing but the rattling of the coach wheels. “Now tell me I’ll find a way out of this. Tell me it will be all right.”

His tone was merry, teasing, but Zoya knew him too well. “It will be all right,” she said with all the conviction she could muster. “We’ll solve this problem as we’ve solved all the others before.” She tilted her head up to look at him. His eyes were closed; a worried crease marred his brow. “Do you believe me?” “Yes.”

“See?” she said as she rested her head against his chest and felt the last of the tremors leave his body. “You’re good at this game, too.”

3

Nina

Nina clutched her knife and tried to ignore the carnage that surrounded her. She looked down at her victim, another body splayed out helpless before her.

“Sorry, friend,” she murmured in Fjerdan. She drove her blade into the fish’s belly, yanked up toward its head, seized the wet pink mess of its innards, and tossed them onto the filthy slats where they would be hosed away. The cleaned carcass went into a barrel to her left, to be cleared by one of the runners and taken off for packaging. Or processing. Or pickling. Nina had no idea what actually happened to the fish and she didn’t much care. After two weeks working at a cannery overlooking the Elling harbor, she didn’t intend to eat anything with scales or fins ever again.

Imagine yourself in a warm bath with a dish full of toffees. Maybe she’d just fill the bathtub with toffee and be really decadent about the endeavor. It could become quite the rage. Toffee baths and waffle scrubs.

Nina gave her head a shake. This place was slowly driving her mad. Her hands were perpetually pruned, the skin nicked by tiny cuts from her clumsy way with the filleting knife; the smell of fish never left her hair; and her back ached from being on her feet in front of the cannery from dawn until dusk, rain or shine, protected from the elements by nothing but a corrugated tin awning. But there weren’t many jobs for unmarried women in Fjerda, so Nina—under the name Mila Jandersdat—had gladly taken the position. The work was miserable but made it easy for their local contact to get her messages, and her vantage point among the fish barrels gave her a perfect view of the guards patrolling the harbor.

There were plenty of them today, roaming the docks in their blue informs. Kalfisk, the locals called them—squid— because they had their tentacles in everything. Elling was one of the few harbors along Fjerda’s rocky northwest coast with easy access to the sea for large vessels. It was where the Stelge River met the Isenvee, and it was known for two things: smuggling and fish. Coalfish, monkfish, haddock; salmon and sturgeon from the river cities to the east; tilefish and silver-sided king mackerel from the deep waters offshore.

Nina worked beside two women—a widow named Annabelle, and Marta, a spinster from Djerholm who was as narrow as a gap in the floorboards and constantly shook her head as if everything displeased her. Their chatter helped to keep

Nina distracted and was a welcome source of gossip and legitimate information, though it could be hard to tell the difference between the two.

“They say Captain Birgir has a new mistress,” Annabelle would begin.

Marta would purse her lips. “With the bribes he takes he can certainly afford to keep her.”

“They’re increasing patrols since those stowaways were caught.”

Marta would cluck her tongue. “Means more jobs but probably more trouble.”

“More men in from Gäfvalle today. River’s gone sour up by the old fort.”

Marta’s head would twitch back and forth like a happy dog’s tail. “A sign of Djel’s disfavor. Someone should send a priest to say prayers.”

Gäfvalle. One of the river cities. Nina had never been there, had never even heard of it until she’d arrived with Adrik and Leoni two months ago on orders from King Nikolai, but its name always left her uneasy, the sound of it accompanied by a kind of sighing inside her, as if the town’s name was less a word than the start of an incantation.

Now Marta knocked the base of her knife against the wooden surface of her worktable. “Foreman coming.”

Hilbrand, the stern-faced foreman, was moving through the rows of stalls, calling out to runners to remove the buckets of fish.

“Your pace is off again,” he snapped at Nina. “It’s as if you’ve never gutted fish before.”

Imagine that. “I’m sorry, sir,” she said. “I’ll do better.”

He cut his hand through the air. “Too slow. The shipment we’ve been waiting for has arrived. We’ll move you to the packing room floor.”

“Yes, sir,” Nina said glumly. She dropped her shoulders and hung her head when what she really wanted to do was break into song. The pay for packing jobs was considerably lower so she had to make a good show of her defeat, but she’d understood Hilbrand’s real message: the last of the Grisha fugitives they’d been waiting for had made it to the Elling safe house at last. Now it was up to Nina, Adrik, and Leoni to get them aboard the Verstoten.

She followed close behind Hilbrand as he led her back toward the cannery.

“You’ll have to move quickly,” he murmured without looking at her. “There’s talk of a surprise inspection tonight.”

“All right.”

“There’s more,” he said. “Birgir is on duty.”

Of course he is. No doubt the inspection was Birgir’s idea. Of all the kalfisk, he was the most corrupt but also the sharpest and most observant. If you wanted a legal shipment to get through the harbor without being trapped forever in customs or if you wanted an illegal bit of cargo to avoid notice, then Captain Birgir was the guard to bribe.

A man without honor, said Matthias’ voice in her head. He should be ashamed.

Nina snorted. If men were ashamed when they should be, they’d have no time for anything else.

“Is something amusing?” Hilbrand asked.

“Just fighting a cold,” she lied. But even Hilbrand’s gruff manner put a pang in her heart. He was broad-shouldered, humorless, and reminded her painfully of Matthias.

He’s nothing like me. What a bigot you are, Nina Zenik. Not all Fjerdans look alike.

“You know what he did to those stowaways,” Hilbrand said. “I don’t have to tell you to be careful.”

“No, you don’t.” Nina was good at her job and she knew exactly what was at stake. Her first morning at the docks, she’d seen Birgir and one of his favorite thugs, Casper, drag a mother and daughter off a whaler bound for Novyi Zem and beat them bloody. The captain had hung heavy chains around their necks weighted with signs that read drüsje—witch. Then he’d doused them in a slurry of waste and fish guts from the canneries and bound them outside the harbor station in the blazing sun. As his men looked on, laughing, the stink and the promise of food drew the gulls. Nina had spent her shift watching the woman trying to shield her daughter’s body with her own, and listening to the prisoners cry out in agony as the gulls pecked and clawed at their bodies. Her mind had spun a thousand fantasies of murdering the harbor guards where they stood, of whisking the mother and daughter to safety. She could steal a boat. She could force a captain to take them far away. She could do something.

But she’d remembered too clearly what Zoya had said to King Nikolai about Nina’s suitability for a deep-cover mission. “She doesn’t have a subtle bone in her body. Asking Nina not to draw attention is like asking water not to run downhill.”

The king had taken a chance on Nina and she would not squander the opportunity. She would not jeopardize the mission. She would not compromise her cover and put Adrik and Leoni at risk. At least not in broad daylight. As soon as the sun set, she had slipped back to the harbor to free the prisoners. They were gone. But to where? And to suffer what horrors? She no longer believed that the worst terror awaiting Grisha at the hands of Fjerdan soldiers was death. Jarl Brum and his witchhunters had taught her too well.

As Nina followed Hilbrand into the cannery, the grind of machinery rattled her skull, the stink of salt cod overwhelming her. She wouldn’t be sorry to leave Elling for a while. The hold of the Verstoten was full of Grisha that her team— or Adrik’s team, really—had helped rescue and bring to Elling. Since the end of the civil war, King Nikolai had diverted funds and resources to support an underground network of informants that had existed for years in Fjerda with the goal of helping Grisha living in secret escape the country. They called themselves Hringsa, the tree of life, after the great ash sacred to Djel. Nina knew Adrik had already received new intelligence from the group, and once the Verstoten was safely on its way to Ravka, Nina and the others would be free to head inland to locate more Grisha.

Hilbrand led her to his office, shut the door behind them, then ran his fingers along the far wall. A click sounded and a second, hidden door opened onto the Fiskstrahd, the bustling street where fishmongers did their business and where a girl on her own might avoid notice by the harbor police by simply vanishing into the crowd.

“Thank you,” Nina said. “We’ll be sending more your way soon.”

“Wait.”Hilbrand snagged her armbeforeshecouldslipinto the sunshine. He hesitated, then blurted out, “Are you really her? The girl who bested Jarl Brum and left him bleeding on a Djerholm dock?”

Nina yanked her arm from his grip. She’d done what she had to do to get her friends free, to keep the secret of jurda parem out of Fjerdan hands. But it was the drug that had made victory possible and it had exacted a terrible price, changing the course of Nina’s life and the very nature of her Grisha power. If we’d never gone to the Ice Court, would Matthias still be alive? Would my heart still be whole? Pointless questions. There was no answer that would bring him back.

Nina fixed Hilbrand with the withering glare she’d learned from Zoya Nazyalensky herself. “I’m Mila Jandersdat. A young widow taking odd jobs to make ends meet and hoping to secure work as a translator. What kind of fool would pick a fight with Commander Jarl Brum?” Hilbrand opened his mouth but Nina continued, “And what kind of podge would risk compromising an agent’s cover when so many lives are on the line?”

Nina turned her back on him and waded into the human tide. Dangerous. A man who lived his life in deep cover shouldn’t be so careless. But Hilbrand was loyal and his own safety relied on his discretion. He’d lost his wife to Brum’s men, the ruthless drüskelle trained to hunt and kill Grisha. Since then, he’d become one of King Nikolai’s most trusted operatives in Fjerda. But loneliness could make you foolish, hungry to speak something other than lies.

It took Nina less than ten minutes to reach the address Hilbrand had given her, another cannery identical to the buildings bracketing it—except for the mural on its western side. At first glance, it looked like a pleasant scene set at the mouth of the Stelge: a group of fishermen casting their nets into the sea as happy villagers looked on beneath a setting sun. But if you knew what to look for, you might notice the white-haired girl in the crowd, her profile framed by the sun as if by a halo. Sankta Alina. The Sun Summoner. A sign that this warehouse was a place of refuge.

The Saints had never been popular among the people of the north—until Alina Starkov had destroyed the Fold. Then altars to her had begun to spring up in countries far outside of Ravka. Fjerdan authorities had done their best to quash the cult of the Sun Saint, labeling it a religion of foreign influence, but still, little pockets of the faithful had bloomed, gardens tended in secret. The stories of the Saints, their miracles and martyrdoms, had become a code for those sympathetic to Grisha. A rose for Sankta Lizabeta. A sun for Sankta Alina. A knight skewering a dragon on his lance might be Dagr the Bold from some children’s tale—or it might be Sankt Juris, who had slain a great beast and been consumed in its flames. Even the tattoos that ran over Hilbrand’s forearms were more than they seemed—a tangle of antlers, often worn by northern hunters, but arranged in circular bands to symbolize the powerful amplifier Sankta Alina had once worn.

Nina knocked on the cannery’s side door and a moment later it swung open. Adrik ushered her inside, his boyish face pale beneath his freckles. Instantly, Nina’s eyes began to water.

“I know,” said Adrik gloomily. “Elling. If the cold doesn’t kill you, the smell will.”

“No fish smells like that. My eyes are burning.”

“It’s lye. Vats of it. Apparently they preserve fish in it as some kind of local delicacy.”

She could almost hear Matthias’ indignant protest, It’s delicious. We serve it on toast. Saints, she missed him. The ache of his absence felt like a hook lodged beneath her heart. The hurt was always there, but in moments like these, it was as if someone had seized hold of the line and pulled.

Nina took a deep breath. Matthias would want her to focus on the mission. “They’re here?”

“They are. But there’s a problem.”

Nina saw Leoni first, bent over a makeshift crate desk beside a row of vats, a lantern lit near her elbow. The twists of her hair were knotted in the Zemeni style, and her dark brown skin was sheened with sweat. On the floor next to her, she’d cracked open her kit—pots of ink and powdered pigments, rolls of paper and parchment. But that made no sense. The emigration documents were long since finished.

Understanding came as Nina’s eyes adjusted and she saw the figures huddled in the shadows—a bearded man in a muskrat-colored coat and a far older man with a thick thatch of white hair. Two little boys peeked out from behind them, eyes wide and frightened.

Leoni glanced up at Nina. “She’s a friend. Don’t worry.”

They didn’t look reassured.

“Jormanen end denam danne näskelle,” Nina said, the traditional Fjerdan greeting to travelers. Be welcome and wait out the storm. It wasn’t totally appropriate to their situation, but it was the best she could offer. The men seemed to relax at the words though the children still looked terrified.

“Grannem end kerjenning grante jut onter kelholm,” the older man said in traditional reply. I thank you and bring only gratitude to your home. Nina hoped that wasn’t true. Ravka didn’t need gratitude, it needed more Grisha. It needed soldiers. She could only imagine what Zoya would make of these recruits.

“Where are the others?” Nina asked Adrik. “They didn’t meet their handler.” “Captured?”

“Possibly.”

“Maybe they had a change of heart,” said Leoni hopefully, opening a bottle of something blue. “It isn’t easy to leave all you love behind.”

“It is when all you love smells like fish and despair,” Adrik grumbled.

“The emigration papers?” Nina asked as gently as she could.

“I’m doing my best,” said Leoni. “We were supposed to have three more arrivals today, all women. That’s the way I wrote up the indentures, for families.”

Nina knew this feeling, this panic. But she also knew Leoni was one of the most talented Fabrikators she’d met.

In recent years, the Fjerdan government had begun to watch their borders more closely and prohibit travel for their citizens. The authorities were on the lookout for Grisha attempting to escape, but they also wanted to slow the tide of people traveling across the True Sea to Novyi Zem seeking better jobs and warmer weather, people willing to brave a new world to live free of the threat of war. Many Ravkans had done the same.

Fjerda’s officials didn’t like to let able-bodied men and prospective soldiers emigrate, and had made the necessary papers almost impossible to forge. That was why Leoni was here. The Zemeni girl was no ordinary forger but a Fabrikator who could match inks and paper at a molecular level.

Nina pulled a clean handkerchief from her pocket and dabbed Leoni’s brow. “You can manage this.”

She shook her head. “I need more time.” “We don’t have it.”

“We might,” said Leoni. She was the same age as Nina, but like many Fabrikators, she had never seen combat. Leoni had spent most of her life in Novyi Zem before traveling to Ravka to train with the Second Army. “We can send word to the Verstoten, ask them to wait until—”

“It’s no good,” Nina said. “That ship has to be out of port by sunset. Captain Birgir is planning one of his surprise raids tonight.”

Leoni let out a long breath, then bobbed her chin at the man in the muskrat-colored coat. “Nina, we’re going to have to pass you off as his wife. And I can rework the emigration papers but there’s no time to fix the indentures.”

It wasn’t ideal. Nina had been working at the harbor for weeks now and there was a chance she’d be recognized. But it was a risk worth taking. “What’s your name?” she asked the man.

“Enok.”

“Those are your sons?”

He nodded. “And this is my father.”

“Well, lucky you, Enok. You’re about to acquire me as a wife. I enjoy long naps and short engagements, and I prefer the left side of the bed.”

Enok blinked and his father looked positively scandalized. Genya had tailored Nina to look as Fjerdan as possible, but the demure ways of northern women were far more exhausting to master.

Nina tried not to pace as Leoni worked and Adrik spoke quietly to the Grisha fugitives. What had happened to the other three Grisha? Nina picked up the abandoned emigration documents. Two women and a girl of sixteen missing. Had they decided a life in hiding was better than an uncertain future in a foreign land? Or had they been taken prisoner? Were they somewhere out there, scared and alone? Nina frowned at the papers. “Were the women really from Kejerut?”

Leoni nodded. “It seemed simpler to keep the town the same.”

Enok’s father made a sign of warding in the air. It was an old gesture, meant to wash away evil thoughts with the strength of Djel’s waters. “Girls go missing from Kejerut.”

Nina shivered as that strange whispering sound filled her head again. Kejerut was only a few miles from Gäfvalle. But it all might mean nothing.

She wished Hilbrand hadn’t mentioned Jarl Brum. Despite all she’d been through, it was a name that still had power over her. Nina had defeated him and his men. Her friends had blown Brum’s secret laboratory to bits and stolen his most valuable hostage. He should have been disgraced. It should have meant an end to his command of the drüskelle and his brutal experiments with jurda parem and Grisha prisoners. And yet somehow, Brum had survived and continued to thrive in the highest ranks of the Fjerdan military. I should have killed him when I had the chance.

You showed mercy, Nina. Never regret that.

But mercy was a luxury Matthias could afford. He was dead after all.

It seems rude to mention that, my love.

What do you expect from a Ravkan? Besides, Brum and I aren’t done.

Is that why you’re here?

I’m here to bury you, Matthias, she thought, and the voice in her head went silent, as it always did when she let herself remember what she’d lost.

Nina tried to shake the thought of Matthias’ body, preserved by Fabrikator craft, bound up in ropes and tarp like ballast, hidden beneath blankets and crates on the sledge that waited back at their boardinghouse. She’d sworn she would take him home, that she would bury his body in the land he loved so that he could find his way to his god. And for nearly two months they had traveled with that body, dragged that grim burden from town to town. She’d had countless opportunities to lay him to rest and say her goodbyes. But she hadn’t taken them.

It has to be the right place, my love. You’ll know it when you see it.

But would she? Or would she just keep marching, unable to let him go?

Somewhere in the distance, a bell rang, signaling the end of the workday.

“We’re out of time,” said Adrik.

Leoni didn’t protest, just stretched and said, “Come dry the ink.”

Adrik waved his hand, directing a gentle gust of warm air over the documents. “It’s nice to be useful.”

“I’m sure you’ll come in very handy when we need to fly kites.”

They exchanged a smile and Nina felt a stab of irritation, then felt like kicking herself for being unfair. If they wanted to fall in love, they should go right ahead and do that.

But as they set out toward the docks, Nina felt her temper spike again when Adrik instructed them to stay alert. Though he was her commanding officer, she’d lost the habit of taking orders during her time in Ketterdam.

Leoni and Adrik led the way to the Verstoten. They were conspicuous but in a way that fit with the tumult of the harbor—a Zemeni woman and her husband, a merchant couple with business on the docks. Nina slipped her arm through Enok’s and hung back slightly with her new family, keeping a careful distance.

She rolled her shoulders, trying to focus, but even that failed to settle her. Her body felt wrong. Back in Os Alta, Genya had tailored her to the very brink of what her skills would allow. Nina’s new hair was slick straight, nearly ice white; her eyes were narrower, the green of her irises changed to the pale blue of a northern glacier. Her cheekbones were higher, her brows lower, her mouth broader. Her thighs were still solid, her waist still thick, but Genya had pushed back Nina’s ears, flattened her breasts, and even changed the set of her shoulders. The process had been painful at times as the bone was altered but Nina didn’t care. She didn’t want to be the girl she’d been, the girl Matthias had loved. If Genya could make her someone new on the outside, maybe Nina’s heart would oblige and beat with a new rhythm, too. Of course, it hadn’t worked. The Fjerdans saw Mila Jandersdat, but she was still Nina Zenik, legendary Grisha and unrepentant killer. She was still the girl who craved waffles and who cried herself to sleep at night when she reached for Matthias and found no one there.

Maybe it was the prospect of returning to the ice that was bothering her, the pressure of finding a resting place for Matthias’ body. She knew Leoni and Adrik didn’t want to raise the issue with her, but they couldn’t be thrilled to be members of a months-long funeral procession.

She felt Enok’s arm tense beneath her fingers and saw that two members of the harbor police were waiting at the gangway that led onto the Verstoten.

“It’s going to be fine,” murmured Nina. “We’ll see you all the way onto the ship.”

“And then what?” Enok asked, voice trembling.

“Once we’re out of the bay, I’ll take a rowboat back to shore with the others. You and your family will travel on to Ravka where you’ll be free to live without fear.”

“Will they take my boys? Will they take them away to that special school?”

“Only if that’s what you wish,” said Nina. “We’re not monsters. Not any more than you are. Now hush.”

But part of her wanted to turn around and march right back to the safe house when she saw that one of the two guards was Birgir’s champion thug, Casper. She tucked her face into her coat collar.

“Zemeni?” Casper asked, glancing at Leoni. She nodded in reply.

Casper gestured to Adrik’s missing arm. “How’d you lose it?”

“Farming accident,” Adrik replied in Fjerdan. He didn’t know much of the language but he could speak bits and pieces without a Ravkan accent, and this particular lie was one he’d told many times. Nearly everyone they met asked about his arm as soon as they saw the pinned sleeve. He’d had to leave the mechanical arm David had fashioned for him back in the capital because it was too recognizable as Grisha handiwork. The guards asked them the usual series of questions— How long had they been in the country? Where had they vis- ited during their stay? Did they have knowledge of foreign agents working inside Fjerda’s borders?—then waved them through with little ceremony.

Now it was Enok’s turn. She gave his arm a squeeze and he stepped forward. Nina could see the sweat beading at his temple, feel the slight tremble in his hands. If she could have snatched the papers away and given them to the guards herself, she would have. But Fjerdan wives always deferred to their husbands.

“The Grahn family.” Casper peered at the papers for an uncomfortably long time. “Indentures? Where will you be working?”

“A jurda farm near Cofton.”

“Hard work. Too hard for the old father there.”

“He’ll be in the main house with the boys,” said Enok. “He’s gifted with a needle and thread and the boys can be runners until they’re old enough for the fields.”

Nina was impressed with how easily Enok lied, but if he’d spent his life hiding as a Grisha he must have had plenty of practice.

“Indentures are difficult to come by,” mused Casper. “My uncle secured them for us.”

“And why is a life breaking your back in Novyi Zem so preferable to one spent doing honest work in Fjerda?”

“I’d live and die on the ice if I had my way,” said Enok with such fervor Nina knew he was speaking the truth. “But jobs are scarce and my son’s lungs don’t like the cold.”

“Hard times all around.” The guard turned to Nina. “And what will you do in Cofton?”

“Sew if I’m able, work the fields if need be.” She dipped her head. She could be subtle, damn it. No matter what Zoya thought. “As my husband wishes.”

Casper continued to look at the papers, smacking them against his palm, and Nina nudged Enok with her elbow. Looking as if he might be sick all over the docks, Enok reached into his pocket and drew out a packet stuffed with Fjerdan currency.

He handed it to Casper who lifted a brow. Then the guard’s face broke into a satisfied smile. Nina remembered him watching the gulls tear at the Grisha left to suffer in chains.

He waved them through. “May Djel watch over you.”

But they hadn’t set foot on the gangway when Nina heard a voice say, “Just a moment.”

Birgir. Couldn’t they have a bit of luck? The sun hadn’t even set. They should have had more time. Enok’s father hesitated on the gangway next to Leoni, and Adrik gave Nina the barest shake of his head. The message was clear: Don’t start trouble.

Birgir stood between Casper and the other guard. He was short for a Fjerdan, his shoulders sloped like a bull’s, and his uniform fit so impeccably, she suspected it had been professionally tailored.

Nina kept behind Enok and whispered to the boys, “Go to your grandfather.” But they didn’t move.

“It was a hard day’s travel for all of us,” Enok said to Birgir amiably. “The boys are eager to get settled.”

“I’ll see your papers first.”

“We just showed them to your man.” “Casper’s eyes aren’t nearly as good as mine.” “But the money—” protested Enok.

“What money was that?”

Casper and the other guard shrugged. “I don’t know about any money.”

“Perhaps,” said Enok’s father, “we could reach a new arrangement?”

“Stay where you are,” said Birgir.

“But our ship is about to depart,” Nina said from behind Enok’s shoulder.

Birgir glanced at the Verstoten, at the boys tugging restlessly on their father’s hands. “They’re going to be a handful cooped up for a sea journey.” Then he looked back at Enok and Nina. “That ship isn’t going anywhere. We’ve an inspection to make.” He gestured to Casper. “There’s something off here. Signal the others.”

Casper reached for his whistle but before he could draw breath to blow, Nina’s arm shot out. Two slender bone shards flew from the sheaths sewn into the forearms of her coat. Everything she wore was laced with them. The darts lodged in Casper’s windpipe, and a sharp wheeze squeaked from his mouth. Nina twisted her fingers and the bone shards turned. The guard dropped to the dock clawing at his neck.

“Casper?” Birgir and the other guard drew their guns.

Nina shoved Enok and the children behind her. “Get them on the boat,” she growled. She hadn’t started this trouble, but she intended to finish it.

“I know you,” Birgir said, eyes narrowing, keeping his gun trained on her.

“That’s a bold statement.”

“You work at the salmon cannery. One of the barrel girls.

I knew there was something wrong about you.” Nina couldn’t help but smile. “Plenty of things.”

“Mila,” Adrik said warningly, using her cover name. As if it mattered now. The time for bribes and negotiations was over. She liked these moments best. When the secrets fell away.

Nina flicked her fingers and the bone shards dislodged from Casper’s windpipe and slid back into the hidden sheaths on her arm. He flopped on the dock, his lips wet with blood, his eyes rolling back in his head as he struggled for breath.

“Drüsje,” Birgir hissed. Witch.

“I don’t like that word,” Nina said, advancing. “Call me Grisha. Call me zowa. Call me death, if you like.”

Birgir laughed. “Two guns are pointed at you. You think you can kill us both before one of us gets a shot off?”

“But you’re already dying, Captain,” she murmured gently. The bone armor the Fabrikators had made for her in Os Alta was a comfort and had proven useful more times than she could count. But sometimes she could feel death in her targets, like now, this man who stood before her, his chin jutting forward, the brass buttons on his fine uniform gleaming. He was younger than she’d realized, his golden stubble patchy in places, as if he couldn’t quite grow a beard. Should she be sorry for him? She was not.

Nina. Matthias’ voice, chiding, disappointed. Perhaps she was doomed to stand on docks and murder Fjerdans. There were worse fates.

“You know it, don’t you?” she went on. “Somewhere inside. Your body knows.” She drew closer. “That cough you can’t shake. The pain you told yourself was a bruised rib. The way food has lost its savor.” In the day’s fading light she saw fear come into Birgir’s face, a shadow falling. It fed her and that strange whispering chorus seemed to rise in her, as if in encouragement, even as Matthias’ voice receded.

“You work in a harbor,” she continued. “You know how easy it is for rats to get into the walls, to eat a place up from the inside.” Birgir’s pistol hand dipped slightly. He was watching her now, closely, not with his sharp, policeman’s eyes but with the gaze of a man who didn’t want to listen, but had to, who must know the end to the story. “The enemy is already inside you, the bad cells eating the others slowly, right there in your lungs. Unusual in a man so young. You’re dying, Captain Birgir,” she said softly, almost kindly. “I’m just going to help you along.”

The captain seemed to wake from a trance. He raised his pistol, but he was too slow. Nina’s power already had hold of that sick cluster of cells within him, and death unfurled, a terrible multiplication. He might have lived another year, maybe two, but now the cells became a black tide, destroying everything in their path. Captain Birgir released a low moan and toppled. Before the other guard could react, Nina flicked her fingers and drove a shard of bone through his heart.

The docks were curiously still. She could hear the waves lapping against the Verstoten’s hull, the high calls of seabirds. Inside her the whispering chorus sounded almost giddy. Then one of the boys began to cry.

For a moment, Nina had stood alone with death on the docks, but now she realized the way the others were watching her—the Grisha fugitives, Adrik and Leoni, even the ship’s captain and his crew leaning over the railing of the ship. Maybe she should have cared, maybe some part of her did.

Nina’s power was frightening, but it had become dear to her. Matthias had accepted the dark thing in her and encouraged her to do the same, but what Nina felt was not acceptance. It was love.

Some men deserve your mercy, Nina. I’ll let you know when I meet one.

Adrik sighed. “I’m not going to miss this town.” He called up to the ship’s crew. “Stop staring and help us get the bodies on board. We’ll dispose of them when we reach open water.”

Nina vowed she would try to do better. Be better. Tomorrow.